"Put Me Back Like They Found Me"

Art by Daisy Patton

“I really don’t want to sue. I just want them to put me back like they found me.”

—Valerie Cliett, sterilized against her will at age 23 after giving birth to her son

Artist Statement by Daisy Patton

Beginning

in the late 19th century, scientists, critical thinkers, and some

progressives believed they had discovered the solution to society’s

ills: eugenics. A movement that still exists in many elements of our

world today, it sought to “breed better humans” through Social

Darwinism. These troubling ideas, which saw upper-class white people as

the sole model of good genetics, transformed into laws that sought to

eliminate “undesirable” people through various means, most especially

reproductive sterilization.

In 1927, Carrie Buck became the test

case for the legal basis of choosing vulnerable, marginalized people

who were deemed unfit. Buck was raped at age seventeen and gave birth

out of wedlock, which led to her institutionalization for supposed

promiscuity and “feeble-mindedness.” This trauma was compounded when her

case was heard by the Supreme Court. Eugenicists' terrible dreams were

fulfilled with the 1927 verdict, and states across the country created

eugenics boards where mostly institutionalized people were subjected to

sterilization often for the simple offense of being poor, disabled, or,

in the case of women, deemed promiscuous (whether true or not). Such

policies were viewed as so successful that Nazi Germany observed and

copied our methods to eliminate entire populations.

Post-World

War II did not see an end to these horrific practices or the eugenics

movement; rather, various states began targeting specific communities of

color as a way to “purify” the country. It is difficult to obtain

precise numbers on how many individuals have been subjected to

sterilization, but through several persistent movements that fought for

reproductive rights, the era of sterilization boards eventually came to

an end, leaving in their wake a wound that never fully heals.

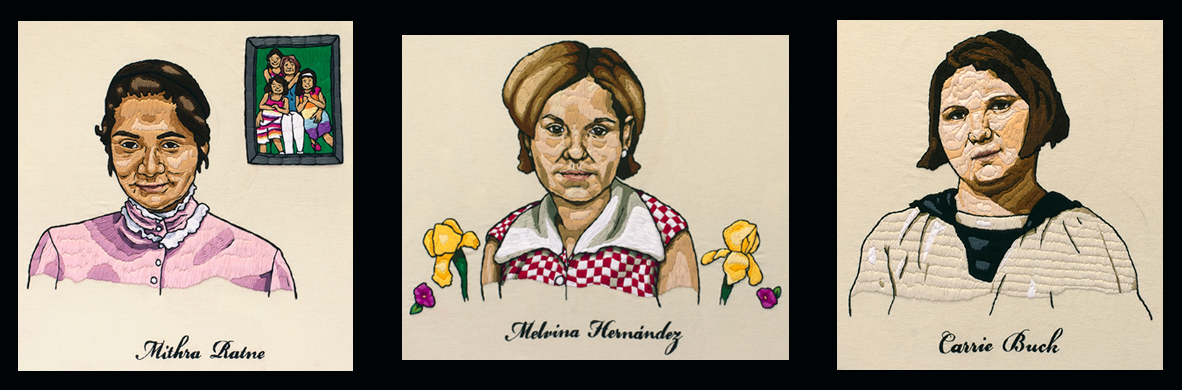

“Put

Me Back Like They Found Me” centers the stories of female survivors of

horrific, regular practices of forced sterilization in the US. I

embroider the portraits of survivors as a nod to domestic labor,

“women’s work,” and thread as a metaphor for life. For living survivors,

the work is a collaboration between the women and myself; each portrait

is designed to contain a chosen element that has significance in their

lives. Hospital gowns display painted text that focus on various

survivors and the sufferings they have endured. It is truly impossible

to understand the tremendous pain and violation forced upon so many

people at the hands of governments, institutions, and doctors in the

name of progress and white supremacy. We as a society owe these

survivors and their memories our care and demand for justice by finally

ending these cruel violations for present and future generations.

One might think that these horrible practices no longer occur, but sadly this has risen up again at ICE facilities.

Read the September, 2020 reporting from Vice News.

On February 8, 2021, Daisy Patton presented a discussion of her exhibit, and was joined by Dr. Virginia Espino, a UCLA historian who produced the film, No Mas Bebes, and Nilmini Rubin, who is the daughter of Mithra Ratne, one of the individuals portrayed in the exhibit.

THE GALLERY IS CLOSED DUE TO THE PANDEMIC.

Art Gallery at the Fulginiti Pavilion

13080 E. 19th Ave. Aurora, CO 80045

Join Daisy Patton for a video tour of the exhibit